How the USSR Radically Reduced Inequality, Even Among its Adversaries

✑ DAVID F. RUCCIO | 1,849 words

╱ October Revolution Centenary Special

"Income inequality was extremely high in Tsarist Russia, then dropped to very low levels during the Soviet period, and finally rose back to very high levels after the fall of the Soviet Union". But there's more; several economists seem to agree that the USSR reduced income inequality (and increase social welfare) in other countries, even among its adversaries in the West.

Even though markets "represent a realm of freedom and independence" compared to "the situation in which individuals found themselves prior to the collapse", the collapse of the USSR led to the "rise of new restrictive relations".

Dr. David F. Ruccio is a renowned marxian economist, professor of economics at the University of Notre Dame, where he has taught since 1982. He is also a member of the Higgins Labor Studies Program and the Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. He blogs, tweets, and contributes to the journal Rethinking Marxism (which he edited for twelve years), Real World Economics Review and Democracy at Work.

Originally published on Ruccio's personal blog and Rethinking Marxism. This is in fact a collection of three of Ruccio's texts, the first two articles originally published on Ruccio's blog on August 16, 2017 and August 25, 2015 and the third (a short extract from a longer paper) in 1992 in Rethinking Marxism.

Russia is back in the news again in the United States, with the ongoing investigation of Russian interference in the U.S. presidential election as well as a growing set of links between a variety of figures (including Cabinet and family members) associated with Donald Trump and the regime of Vladimir Putin.

This year is also the hundredth anniversary of the October Revolution, which sought to create the conditions for a transition to communism in the midst of a society characterized by various forms of feudalism, peasant communism, and capitalism. But we shouldn’t forget that, in addition, the Red Century has clearly left its mark on the political economy of the West, including the United States — both in the early years, when the “communist threat” undoubtedly led to reforms associated with a more equal distribution of income, and later, when the Fall of the Wall reinforced the neoliberal turn to privatization and deregulation [more on this below].

Now we have a third reason to think about Russia, which happens to intersect with the first two concerns. A new study of income and wealth data by Filip Novokmet, Thomas Piketty, Gabriel Zucman reveals just how much has changed in Russia from the time of the tsarist oligarchy through the Soviet Union to rise of the new oligarchy during and after the “shock therapy” that served to create a new form of private capitalism under Putin.

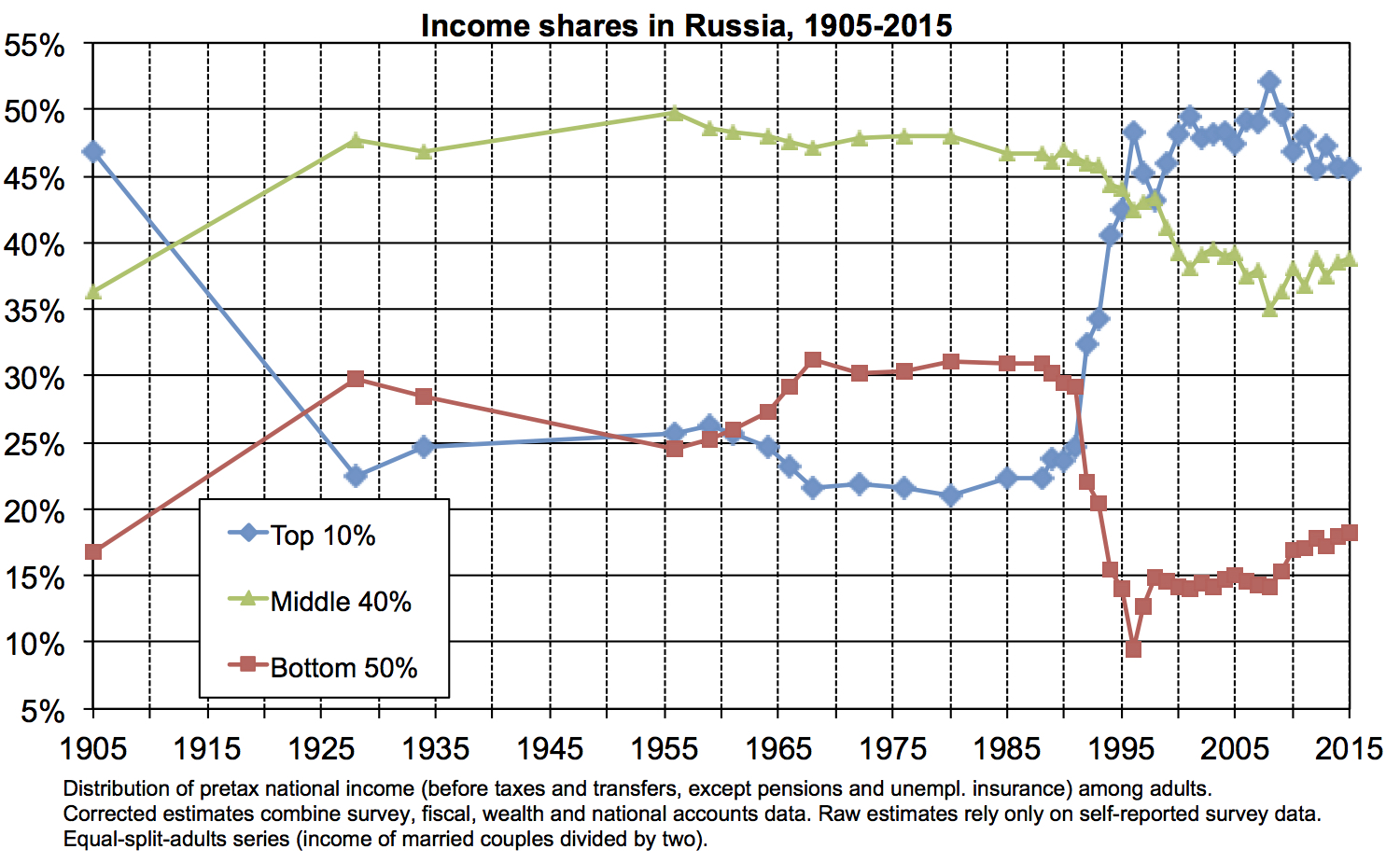

As is clear from the chart, income inequality was extremely high in Tsarist Russia, then dropped to very low levels during the Soviet period, and finally rose back to very high levels after the fall of the Soviet Union. Thus, for example, the top 1-percent income share was somewhat close to 20 percent in 1905, dropped to as little as 4-5 percent during the Soviet period, and rose spectacularly to 20-25 percent in recent decades.

The data sets used by Novokmet et al. reveal a level of inequality under the new oligarchs that is much higher than was apparent using survey data—a top 1-percent income share that is more than double for 2007-08.

Novokmet et al. also show that the income shares of the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent moved in exactly opposite directions after the privatization of Russian state capitalism in the early 1990s. While the top 10-percent income share rose from less than 25 percent in 1990-1991 to more than 45 percent in 1996, the share of the bottom 50 percent collapsed, dropping from about 30 percent of total income in 1990-1991 to less than 10 percent in 1996, before gradually returning to 15 percent by 1998 and about 18 percent by 2015.

In comparison to other countries, Russia was much more equal during the Soviet period and, by 2015, had approached a level of inequality higher than that of France and comparable only to that of the United States.

Finally, Novokmet et al. have been able to estimate the enormous growth of private wealth under the new oligarchy, especially the wealth that was captured by a tiny group at the very top and is now owned by Russia’s billionaires. As the authors explain,

Clearly, there is nothing “natural” about the distribution of income and the ownership of wealth. This new study demonstrates that different economic structures and political events create fundamentally different levels of inequality in both income and wealth, both within and between countries.

The Russian experience is a perfect example how inequality can fall and then, later, be reversed with radical economic and political transformations—thus creating a new oligarchy that dominates the national political economy and seeks to intervene in other countries.

Not unlike the United States.

RELATED

Economist Richard D. Wolff (who has worked with Ruccio in past decades) explains the nature of the USSR in his radio show Economic Update. "It wasn't socialism in the sense that Marx and others had long written about."

Economist Michael Roberts manages to sum up the (economic) history of the USSR in a relatively short post on his blog, covering the (economic) roots of the Russian Revolution, the crises, conflicts and famines that plagued the Soviet Union afterwards, its enormous economic growth in the fifties and sixties and its eventual collapse. Modestly titled "The Economic Revolution: some economic notes".

‟The Red Century has clearly left its mark on the political economy of the West.

"Income inequality was extremely high in Tsarist Russia, then dropped to very low levels during the Soviet period, and finally rose back to very high levels after the fall of the Soviet Union". But there's more; several economists seem to agree that the USSR reduced income inequality (and increase social welfare) in other countries, even among its adversaries in the West.

Even though markets "represent a realm of freedom and independence" compared to "the situation in which individuals found themselves prior to the collapse", the collapse of the USSR led to the "rise of new restrictive relations".

Dr. David F. Ruccio is a renowned marxian economist, professor of economics at the University of Notre Dame, where he has taught since 1982. He is also a member of the Higgins Labor Studies Program and the Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. He blogs, tweets, and contributes to the journal Rethinking Marxism (which he edited for twelve years), Real World Economics Review and Democracy at Work.

Originally published on Ruccio's personal blog and Rethinking Marxism. This is in fact a collection of three of Ruccio's texts, the first two articles originally published on Ruccio's blog on August 16, 2017 and August 25, 2015 and the third (a short extract from a longer paper) in 1992 in Rethinking Marxism.

▰

Russia is back in the news again in the United States, with the ongoing investigation of Russian interference in the U.S. presidential election as well as a growing set of links between a variety of figures (including Cabinet and family members) associated with Donald Trump and the regime of Vladimir Putin.

This year is also the hundredth anniversary of the October Revolution, which sought to create the conditions for a transition to communism in the midst of a society characterized by various forms of feudalism, peasant communism, and capitalism. But we shouldn’t forget that, in addition, the Red Century has clearly left its mark on the political economy of the West, including the United States — both in the early years, when the “communist threat” undoubtedly led to reforms associated with a more equal distribution of income, and later, when the Fall of the Wall reinforced the neoliberal turn to privatization and deregulation [more on this below].

Now we have a third reason to think about Russia, which happens to intersect with the first two concerns. A new study of income and wealth data by Filip Novokmet, Thomas Piketty, Gabriel Zucman reveals just how much has changed in Russia from the time of the tsarist oligarchy through the Soviet Union to rise of the new oligarchy during and after the “shock therapy” that served to create a new form of private capitalism under Putin.

As is clear from the chart, income inequality was extremely high in Tsarist Russia, then dropped to very low levels during the Soviet period, and finally rose back to very high levels after the fall of the Soviet Union. Thus, for example, the top 1-percent income share was somewhat close to 20 percent in 1905, dropped to as little as 4-5 percent during the Soviet period, and rose spectacularly to 20-25 percent in recent decades.

The data sets used by Novokmet et al. reveal a level of inequality under the new oligarchs that is much higher than was apparent using survey data—a top 1-percent income share that is more than double for 2007-08.

Novokmet et al. also show that the income shares of the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent moved in exactly opposite directions after the privatization of Russian state capitalism in the early 1990s. While the top 10-percent income share rose from less than 25 percent in 1990-1991 to more than 45 percent in 1996, the share of the bottom 50 percent collapsed, dropping from about 30 percent of total income in 1990-1991 to less than 10 percent in 1996, before gradually returning to 15 percent by 1998 and about 18 percent by 2015.

In comparison to other countries, Russia was much more equal during the Soviet period and, by 2015, had approached a level of inequality higher than that of France and comparable only to that of the United States.

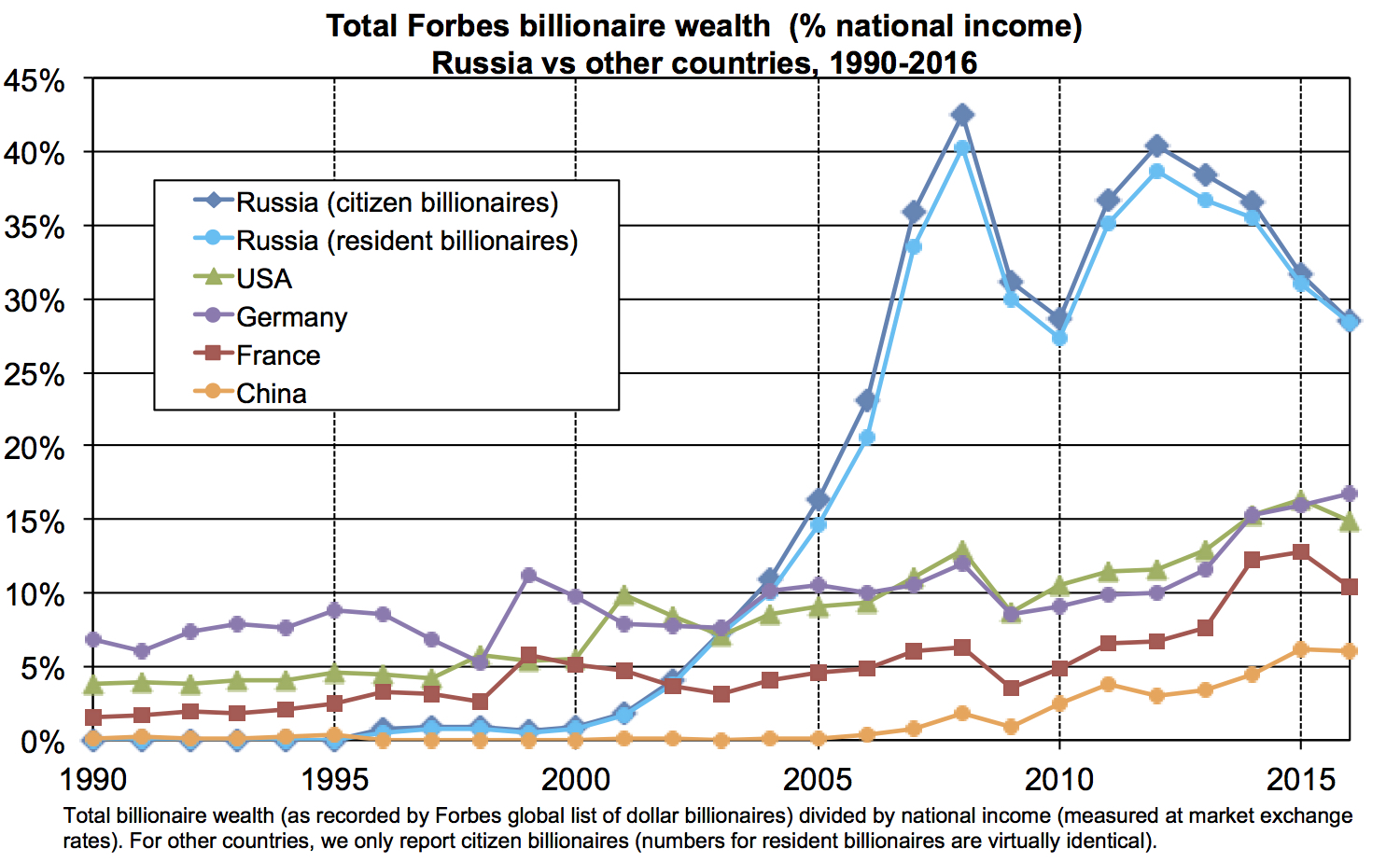

Finally, Novokmet et al. have been able to estimate the enormous growth of private wealth under the new oligarchy, especially the wealth that was captured by a tiny group at the very top and is now owned by Russia’s billionaires. As the authors explain,

"The number of

Russian billionaires—as registered in international rankings such

as the Forbes list—is extremely high by international standards.

According to Forbes, total billionaire wealth was very small in

Russia in the 1990s, increased enormously in the early 2000s, and

stabilized around 25-40% of national income between 2005 and 2015

(with large variations due to the international crisis and the sharp

fall of the Russian stock market after 2008). This is much larger

than the corresponding numbers in Western countries: Total

billionaire wealth represents between 5% and 15% of national income

in the United States, Germany and France in 2005-2015 according to

Forbes, despite the fact that average income and average wealth are

much higher than in Russia. This clearly suggests that wealth

concentration at the very top is significantly higher in Russia than

in other countries."

Clearly, there is nothing “natural” about the distribution of income and the ownership of wealth. This new study demonstrates that different economic structures and political events create fundamentally different levels of inequality in both income and wealth, both within and between countries.

The Russian experience is a perfect example how inequality can fall and then, later, be reversed with radical economic and political transformations—thus creating a new oligarchy that dominates the national political economy and seeks to intervene in other countries.

Not unlike the United States.

Better Equal than Red

August 25, 2015↗

August 25, 2015↗

"The idea is

simple: the presence of the ideology of socialism (abolition of

private property) and its embodiment in the Soviet Union and other

Communist states made capitalists careful: they knew that if they

tried to push workers too hard, the workers might retaliate and

capitalists might end up by losing all."

The idea reminds me of an argument Etienne Balibar made many years ago (unfortunately, I can no long remember or find the original source but here’s a link [pdf] to one version of it)—that the “European project” was more progressive during the Cold War in the sense that the welfare state was constructed, by forces from above and below, as a response to the Soviet model of socialism, in order to prevent the working classes from adopting a communist ideology. (Since then, as Balibar has recently argued, the European project has fundamentally changed, as it has been assimilated by globalized finance capitalism and, under German hegemony, a strategy of industrial competitiveness based on low wages.)

Milanovic discusses some recent empirical work on three channels through which socialism “disciplined” income inequality under capitalism: (a) ideology/politics (e.g., the electoral importance of Communist and some socialist parties), (b) trade unions (some of which were affiliated with Communist or Labor parties), and (c) the “policing” device of the Soviet military power. He then offers his own analysis:

"Communism, was a

global movement. It does not require much reading of the literature

from the 1920s to realize how scared capitalists and those who

defended the free market were of socialism. After all, that’s why

capitalist countries militarily intervened in the Russian Civil War,

and then imposed the trade embargo and the cordon sanitaire on the

USSR. Not a sort of policies you would do if you were not

ideologically afraid (because militarily the Soviet Union was then

very weak). The threat intensified again after the World War II when

the Communist influence through all three channels was at its peak.

And then it steadily declined so much that by mid-1970s, it was

definitely small. The Communist parties reached their maximum

influence in the early 1970s but Eurocomunism had already expunged

from its program any ideas of nationalization of property. It was

rapidly transforming itself into social democracy. The trade unions

declined. And both the demonstration effect and the fear of the

Soviet Union receded. So capitalism could go back to what it would be

doing anyway, that is to the levels of inequality it achieved at the

end of the 19th century. “El periodo especial” of capitalism was

over."

He admits the implication of such a story may be rather unpleasant:

"left to itself,

without any countervailing powers, capitalism will keep on generating

high inequality and so the US may soon look like South Africa."

This is not to suggest we need another Cold War for the United States not to move even closer to looking like South Africa. But it does mean there will be a significant move from above toward more democracy and less inequality only if there’s a real threat to move outside of capitalism from below.

Failure of Socialism, Future of Socialists?

1992↗

In the case of Eastern Europe and the ex-Soviet Union, it is clear that, at least on some level, markets - specially markets for goods and services - represent a realm of freedom and independence. This is especially true when compared with the situation in which individuals found themselves prior to the collapse. Within the existing socialist societies, where the system of exchange was relatively undeveloped, the relations among individuals appeared to be more “personal.” Family ties and friendships were important. In many cases, individuals needed to be related to or to know someone in order to gain access to housing or a decent job. Patronage appears to have been rampant. While seemingly more personal, the relations among individuals under the old regimes corresponded to certain definitions: members of the Party and nonmembers; state-appointed managers of enterprises and wage laborers; state marketing boards and agricultural producers; central power and individual republics; and so on. With the emergence of markets, many of the ties of personal dependence were quickly disrupted: the Party was thrown from power; central decision-making was challenged by newly independent nations; contractual obligations under the plan were ignored; and so on. Individuals thus came to experience a new independence - or, at least, indifference - with the development of markets and a system of money and exchange-values.

Elsewhere (in the Communist Manifesto) Marx summarized this new-found freedom in a “melting” vision of the social relations that characterize a system of developed exchange. “Solid” personal ties of dependence “melt into air” and individuals become “free to collide with one another and to engage in exchange within this freedom.” Individuals acquire the freedom to buy, sell, and consume use-values. This is the sense of freedom that is celebrated not only by the individuals who protested the old regimes but also by their “democratic” leaders.

But the analysis does not stop there. Marx goes on to argue that the disintegration of personal dependence is accompanied by the rise of new restrictive relations. Individuals are seen to be entirely free and independent only by abstracting from these new “conditions of existence” of exchange. The old ties of personal dependence are replaced by a new “definedness” of the rules of social interaction, forms of social interaction that appear to be independent of those individuals. New conditions emerge that appear to be “not controllable by individuals.” Inflation is a good example: the increase in prices for consumer goods and the decline in purchasing power cannot be easily attributed to the actions of any single individual or group.

From this perspective, relations of personal dependence are not simply dissolved and replaced by freedom and independence. Instead, relations of dependence are constituted in new ways and on a new, more general foundation: “individuals [still] come into contact with one another only in determined ways.” Instead of depending on one another, individuals come to depend on conditions that are independent of them. They come to ruled by “abstractions.” For example, inflation is said to be caused not by individuals but by the extent of “disequilibrium” of markets and the government budget. Individuals become increasingly dependent on the forces of “supply and demand.” It is in this sense that a society with a developed system of commodity exchange can be understood precisely as a “process without a subject.”

1992↗

In the case of Eastern Europe and the ex-Soviet Union, it is clear that, at least on some level, markets - specially markets for goods and services - represent a realm of freedom and independence. This is especially true when compared with the situation in which individuals found themselves prior to the collapse. Within the existing socialist societies, where the system of exchange was relatively undeveloped, the relations among individuals appeared to be more “personal.” Family ties and friendships were important. In many cases, individuals needed to be related to or to know someone in order to gain access to housing or a decent job. Patronage appears to have been rampant. While seemingly more personal, the relations among individuals under the old regimes corresponded to certain definitions: members of the Party and nonmembers; state-appointed managers of enterprises and wage laborers; state marketing boards and agricultural producers; central power and individual republics; and so on. With the emergence of markets, many of the ties of personal dependence were quickly disrupted: the Party was thrown from power; central decision-making was challenged by newly independent nations; contractual obligations under the plan were ignored; and so on. Individuals thus came to experience a new independence - or, at least, indifference - with the development of markets and a system of money and exchange-values.

Elsewhere (in the Communist Manifesto) Marx summarized this new-found freedom in a “melting” vision of the social relations that characterize a system of developed exchange. “Solid” personal ties of dependence “melt into air” and individuals become “free to collide with one another and to engage in exchange within this freedom.” Individuals acquire the freedom to buy, sell, and consume use-values. This is the sense of freedom that is celebrated not only by the individuals who protested the old regimes but also by their “democratic” leaders.

But the analysis does not stop there. Marx goes on to argue that the disintegration of personal dependence is accompanied by the rise of new restrictive relations. Individuals are seen to be entirely free and independent only by abstracting from these new “conditions of existence” of exchange. The old ties of personal dependence are replaced by a new “definedness” of the rules of social interaction, forms of social interaction that appear to be independent of those individuals. New conditions emerge that appear to be “not controllable by individuals.” Inflation is a good example: the increase in prices for consumer goods and the decline in purchasing power cannot be easily attributed to the actions of any single individual or group.

From this perspective, relations of personal dependence are not simply dissolved and replaced by freedom and independence. Instead, relations of dependence are constituted in new ways and on a new, more general foundation: “individuals [still] come into contact with one another only in determined ways.” Instead of depending on one another, individuals come to depend on conditions that are independent of them. They come to ruled by “abstractions.” For example, inflation is said to be caused not by individuals but by the extent of “disequilibrium” of markets and the government budget. Individuals become increasingly dependent on the forces of “supply and demand.” It is in this sense that a society with a developed system of commodity exchange can be understood precisely as a “process without a subject.”

RELATED

Economist Richard D. Wolff (who has worked with Ruccio in past decades) explains the nature of the USSR in his radio show Economic Update. "It wasn't socialism in the sense that Marx and others had long written about."

Economist Michael Roberts manages to sum up the (economic) history of the USSR in a relatively short post on his blog, covering the (economic) roots of the Russian Revolution, the crises, conflicts and famines that plagued the Soviet Union afterwards, its enormous economic growth in the fifties and sixties and its eventual collapse. Modestly titled "The Economic Revolution: some economic notes".

Comments

Post a Comment

Your thoughts...