Trump’s Deja Vu China Trade War (Part 2)

✑ JACK RASMUS` ╱ ± 25 minutes

In 2018 China and the US came to the brink of a bona fide trade war and then halted at the precipice. What was the real US priority? Whose trade war was it? Will a final deal be reached coming March?

Summary Part I

The key will be how far China is willing to go with tech concessions.

In 2018 China and the US came to the brink of a bona fide trade war and then halted at the precipice. What was the real US priority? Whose trade war was it? Will a final deal be reached coming March?

From: Jack Rasmus, Jan 20 2019. ╱ About the author(+)

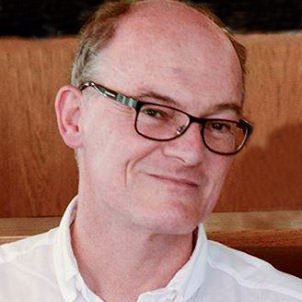

Dr. Jack Rasmus, Ph.D Political Economy, teaches economics and politics at St. Mary’s College in California. He is the author and producer of the various nonfiction and fictional workers, including the recently published ‘Central Bankers at the End of Their Ropes: Monetary Policy and the Coming Depression’, Clarity Press, August 2017; ‘Looting Greece: A New Financial Imperialism Emerges’, Clarity Press, October 2016; and ‘Systemic Fragility in the Global Economy’, Clarity Press, January 2016. His website is: http://www.kyklosproductions.com and twitter handle, @drjackrasmus..

| This writer was asked to write a comprehensive article on the Trump trade ‘war’ in general, and specifically in relation to China. That article is appearing in the latest edition of the World Review of Political Economy, published and edited in Beijing. It’s entitled ‘Trump’s Deja Vu China Trade War’. What follows is the second part of that article. Part 1, which addresses events from the initiation of Trump’s trade offensives in March 2018, was posted before here. |

|---|

Summary Part I

In 2018 China and the US came to the brink of a bona fide trade war and then halted at the precipice. At the G20 meeting in Buenos Aires in late November 2018, Trump and China President, Xi, met offsite. The outcome was an agreement to put off further escalation of tariffs on both sides for another 90 days during which their trade teams would meet to try to seek a resolution. Economies of both countries were showing signs of growing weakness and instability by November. The indicators worsened notably in December. Trump agreed to postpone US announced tariffs on an additional $200 billion of China imports, effective January 1, 2019, and suspend increases on already existing tariffs from 10% to 25%, also scheduled for January 1. China agreed as well to postpone further its scheduled tariffs. In early weeks of January 2019, middle level officials of both China and the US began meeting to discuss details for subsequent higher level negotiations set for Washington on January 30, 2019.

Unlike Trump’s trade ‘war’ with US allies, which has always been ‘phony’ (see Part 1 of this article). Trump never envisioned major changes in US trade relations with US allies, starting with South Korea, then NAFTA trade partners, Mexico and Canada. Tariffs on steel and aluminum were offset by more than 3000 exemptions announced by the Trump administration. Tariffs on European autos, threatened by Trump, were suspended. And trade negotiations with Japan were left unscheduled.

Before the November 2018 US midterm Congressional elections, Trump sought just token adjustments to US-ally trade relations that he then exaggerated and boasted to his US domestic political base, claiming his ‘America First’ economic nationalism policies were delivering results. China-US trade was another matter.

On the surface, the China-US dispute appeared as the US attempting to reduce the trade deficit with China—although that US trade deficit with China had not changed much for the past several years. A second apparent US objective was the US long-standing demand that China open its markets to US business, which meant that China should allow US companies a greater than 50% ownership of their operations in China, especially US banks and financial corporations. But reducing the trade deficit and opening China markets were secondary objectives. The primary US objective, that became increasingly apparent over the course of 2018, was to prevent, or at least slow, China’s ‘2025’ technology development program. That program focused on next generation technologies like AI, cybersecurity and 5G wireless—the technologies of the future that new industries would be built upon. And, equally important, the technologies that would determine military dominance by 2030.

What follows is Part II of the analysis of Trump’s Déjà vu China-US trade ‘war’ from last March 2018 through mid-January 2019.

The Real Trade War: China Technology

Trump’s trade strategy in relation to China has always been to pressure China on technology transfer and slow its nextgen technology development. Reducing the US-China trade deficit and getting China to open its markets to US financial interests have been objectives as well, but of secondary importance.

Early in 2018 China signaled publicly it would buy $100 billion a year more US products and open its markets to US corporate majority 51% or more ownership. It even granted 51% ownership to select global companies while negotiations with the US were underway. But it refused to make concessions on the technology issue. US defense companies, the Pentagon, the US military-industrial complex interests on the one hand, and US banks on the other, are the major players in determining US trade policy.

Throughout 2018 US trade policy is best described as schizophrenic. Was it Trump driving policy? His anti-China neocons and hawk advisors–Lighthizer, Navarro, and later John Bolton, appointed to the post of National Security Advisor to Trump in 2018, who later joined the administration? Was it Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, who represents US banking and multinational corporate interests on the US trade team? Larry Kudlow, Trump’s interface to his domestic base? And what about Jared Kushner, son-in-law of Trump who has Trump’s closest ear, who has been serving as Trump’s interface to the three major factions on the US trade team? Throughout 2018, the factions contended for Trump’s support, with influence shifting and fluid among the various factions.

Pre-negotiations with China started in early March with Trump’s announcement of the steel-aluminum tariffs. After the tariff announcement, Trump began tweeting the idea that China should reduce its imports to the US by $100 billion. A day after the Office of US Trade Representative (OUST report) was issued by chief Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, Trump announced tariffs of $50 billion on China imports recommended by Lighthizer. However, a window of at least 60 days was required before any definition of the $50 billion or actual implementation by the US might occur, giving ample time for unofficial negotiations to occur between the countries’ trade missions. (Technically, the US could even wait for another six months before actually implementing any tariffs). Announcing intent to a dollar amount of tariffs is one thing; providing a list and definition of what goods would be tariffed is another; and setting a date they would take effect is still another.

China immediately sent its main trade negotiator, Liu He, to Washington and assumed a cautious, almost conciliatory approach at first. China responded initially in March with a modest $3 billion in tariffs on US exports. It also made it clear the $3 billion was in response to US steel and aluminum tariffs previously announced by Trump, and not Trump’s $50 billion tariff threat specifically targeting China. But China noted more action could follow, as it forewarned it was considering additional tariffs of 15% to 25% on US products, especially agricultural, in response to Trump’s $50 billion announcement.

China was waiting to see the US details. At the same time in April it signaled it was willing to open China brokerages and insurance companies to US 51% ownership (and possibly even 100% within three years). It also announced it would buy more semiconductor chips from the US instead of Korea or Taiwan. It was all a carefully crafted public response, designed not to escalate trade negotiations with the Trump administration prematurely. A series of token concessions and minimal tariff responses.

Behind the scenes China and US trade representatives continued to negotiate. By the end of March, all that had actually had occurred was Trump’s announcement of $50 billion in tariffs on China imports, but without details, plus China’s $3 billion token response to prior US steel-aluminum tariffs. From there, however, events began to deteriorate.

On April 3, 2018 Trump defined his threat of $50 billion of tariffs—25% on a wide range of 1300 of China’s consumer and industrial imports to the US. It was Lighthizer’s OUST Report’s recommended March list that launched Trump’s trade offensive with China. Influential business groups in the US, like the Business Roundtable, US Chamber of Commerce, and National Association of Manufacturers immediately criticized the move, calling for the US instead to work with its allies to pressure China to reform—not to use tariffs as the trade reform weapon. The anti-China hardline US factor brushed aside the criticism.

China now responded more firmly, promising an equal tariff response, declaring it was not afraid of a trade war with the US. That was an invitation for a Trump tweet and declaration he believed the US would not “lose a trade war” with China and maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to have one. He suggested that another $100 billion in US tariffs might get China’s attention.

China’s initial $3 billion tariffs, and China’s suggestion of more billions of 15%-25% tariffs, targeted US companies and agricultural production in Trump’s Midwest political base. This may have especially aggravated Trump, disrupting his plans to mobilize that base for domestic political purposes before the November 2018 elections. Trump’s typical approach to negotiating—employed repeatedly during his private business dealings before being elected—is to never let his adversary ‘one up’ him, as they say. He always keeps raising the stakes until the other side stops matching his demands. Then he negotiates back to original positions, controlling the negotiating agenda and maintaining the upper hand in the process.

In response to the ‘tit for tat’ tariff threats, the US stock markets plummeted during the first week of April. Trump advisors, Larry Kudlow and Steve Mnuchin, intervened publicly to dampen the effect of Trump’s remarks on the markets. Kudlow tried to assure investors, “These are just first proposals…I doubt that there will be any concrete actions for several months”. Kudlow said negotiations were continuing. The stock markets recovered again.

But who were investors supposed to believe—Trump or his advisors? They seemed to be talking in different directions. And how long would investors continue to believe the Kudlows and others that matters (and Trump) were under control, and there would be no trade war? China representatives noted that, contrary to Kudlow’s assurances to US markets and investors, there were no ongoing discussions between the two countries.

By the end of the first week of April, US trade objectives and strategy was becoming increasingly murky: US multinational businesses restated what they wanted was more access to China markets. US defense establishment, NSA and the Pentagon, and the Trump administration ‘hawks’—Lighthizer, John Bolton and Peter Navarro—retorted they wanted an end to strategic technology transfer to China—both from US companies doing business in China and from China companies purchasing or partnering with American companies in the US.

It appeared what Trump himself wanted anything was something to exaggerate and brag about to his domestic political base emphasizing nationalist themes—to keep his popular ratings growing, to ensure Republican retention of seats in Congress in the November elections, and to whip up his base.

So what was the real US priority? Whose trade war was it? The neocons and China hawks aligned with the US military-industrial complex? Midwest agribusiness and manufacturing interests? Or US finance capital wanting to escalate its penetration of China markets?

However, by mid-April it was all still talk, with tariffs actions on paper, and not yet implemented. The next step would be defining the announced tariffs in detail. Announcing tariffs was only like waving a gun, to use a metaphor. Defining the tariffs was like loading a gun, putting the ‘safety’ lock on, but not yet pulling the trigger. Tariff implementation dates were when the shoot-out would really begin.

As of mid-April the negotiations by trade representatives continued in the background, while US capitalists in the Business Roundtable and other prime corporate organizations added their input to the public commentary process that was scheduled to continue in the US until May 22.

US Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, went to Beijing in the weeks prior to May 22. He returned declaring there was an agreement. Mnuchin kicked Peter Navarro, one of the hawks, from the US trade team. The China hawks and military industrial complex immediately responded, with help of their friends in Congress. They went after China’s ZTE corporation doing business in the US, charging it with technology espionage and transfer. The tech faction on the US trade team took over from Mnuchin. Navarro was put back. Any tentative deal was scuttled.

What happened in the subsequent six months from June to November 2018 was a steady escalation of threats, and subsequent actions, by Trump to raise tariffs, while he simultaneously kept saying his relationship with China president Xi was great and he expected a trade deal at some point: His response to China’s $50 billion tariff announcement—the counter to Trump’s $100 billion more tariffs—was to publicly declare the US should consider an additional $100 billion in tariffs. The additional $100 billion were implemented thereafter.

China again responded tit-for-tat, as its Commerce Ministry spokesman, Gao Feng, declared it would not hesitate to put in place ‘detailed countermeasures’ that didn’t ‘exclude any options’. And, in the most ominous comment to date, it was made clear that should Trump impose the additional $100 billion, ‘China would not negotiate’! And as China Foreign Ministry spokesman, Geng Shuang, following up Gao Feng, indicated in an official news briefing, “The United States with one hand wields the threat of sanctions, and at the same time says they are willing to talk. I’m not sure who the United States is putting on this act for”…Under the current circumstances, both sides even more cannot have talks on these issues”.

Trump’s $150 billion in tariffs on China was played to his domestic political base, in the weeks prior to the November midterm US elections, as evidence of his tough policy of US economic nationalism. Trump further announced reaching an agreement with Mexico and Canada replacing the NAFTA free trade deal—exaggerating and spinning the new terms and conditions as major improvements while, in fact, the details were token much like the prior changes to the US-South Korean free trade agreement. No new tariffs were implemented on Mexican goods imports to the US.

Trump threatened to raise tariffs on the second $100 billion implemented, from 10% to 25% and threatened another 25% on an additional $200 billion in China imports. Still no China agreement to negotiate.

By the early fall 2018 it was clear that the China hawks—Lighthizer, the military-industrial complex-the Pentagon & Co.—were in control of Trump trade policy. Regardless of China concessions on reducing the trade deficit or granting 51% access to its markets, their primary demand was slowing (or ideally subverting) China technology develop—stopping tech transfer in China and elsewhere in the US, as well as among US allies. The side-lining of Mnuchin over the summer, the restoration of Navarro to the trade team, and the adding of notorious anti-China hawk, John Bolton, all strengthened the tech development faction, led by Lighthizer, on the US trade team. They were in effect in control as the US midterm elections approached.

Following the November US elections, a meeting was now possible. The G20 nations gathering in Buenos Aires scheduled for late November presented the opportunity. Intense maneuvering occurred between the anti-China technology hawks and the Mnuchin bankers-multinational corporations factions. Lighthizer released a new report criticizing China tech policy and appeared to have the upper hand and opposed a meeting between Trump and China president, Xi, at a side venue dinner in Buenos Aires. That reflected a new effort and breakthrough by the Mnuchin faction of big US banks, tech, and aerospace corporations. From mid-October through November the US stock markets began a precipitous fall, which would continue through December, and amount to the worst stock correction since 2008 and even 1931. That financial and the real slowing of the US housing, construction, and auto industries likely shifted Trump administration strategy. The momentum of negotiations strategy began to shift from the Ligthizer faction.

Elements of Trump Trade Strategy

Apart from the three main objectives of Trump China trade policy noted—i.e. China purchases of more US goods, opening markets to 51% ownership for banks and other US corporations, and the nextgen tech development issue—there are various additional objectives behind the strategy.

First, the steel-aluminum tariffs that launched the Trump trade offensive in March 2018 were a signal to US competitors that they should prepare to ‘come to the table’ and renegotiate current trade arrangements, since the US now plans to change the rules of the game again—just as Reagan and Nixon did before in the 1970s and 1980s. But once they ‘came to the table’, the changes in rules of the game with regard to trade relations with US allies did not result in a fundamental restructuring of the US-allies trade relations. The South Korean deal (see Part 1 of this article), the following revised NAFTA treaty, the suspension of negotiations on auto and other tariffs with Europe and Japan, plus the thousands of exemptions to steel and other tariffs allowed by the Trump administration to date all reveal that trade renegotiation with US allies is mostly for show. However, the effort throughout 2018 all made for good campaign speech ‘economic nationalist’ hyperbole in an election year.

A second development impacting Trump trade strategy has to do with the inevitable slowing of the US real economy in 2019-20. The floodgates of fiscal policy have been reopened in 2018 with Trump’s $4.5 trillion corporate and investor tax cuts, plus hundreds of billions $ more in defense and war spending hikes. Annual deficits of more than $1 trillion a year for another decade are now baked into the US budget. The deficits in turn have required the Federal Reserve US central bank to raise interest rates to fund those annual trillion dollar and more deficits and debt. It is becoming increasingly clear that the Trump tax cuts have not stimulated real US economic growth very much. Most of the $4.5 trillion business-investor tax cuts are going toward buying back corporate stock ($590 billion forecast 2018 by Goldman Sachs), paying out more dividends ($400 billion plus forecast), and financing record levels of merger & acquisition deals ($1.2 trillion in 2018)..

Third, Trump trade policy comes as global trade has been slowing. Global commodity prices are in retreat once again. 2017’s much hyped ‘synchronized’ global recovery is falling apart—in Europe, Japan and key emerging market economies as well. Another recession is coming, possibly as early as late 2019 and certainly no later than 2020. So US trade policy is shifting, attempting to ensure that US business interests retain their share of what will likely be a slower growing (or even declining) world trade pie. Trump and US business are repositioning before the global cycle next turns down.

US domestic and global economic objectives are not the only forces influencing Trump’s trade policy. There are just as important US political objectives behind it as well.

Less obvious perhaps is Trump’s leveraging of trade policy and nationalist themes as a way to agitate and mobilize his base, in preparation to counter the Mueller investigation once it’s concluded. As a possible Mueller indictment of Trump approaches, Trump has been clearly preparing his base. He is also cleaning house within his administration, surrounding himself with like-minded aggressive conservatives, former Neocons, and various sycophants—in anticipation of the ‘street fight’ he’s preparing for with the traditional liberal elite in the US once he (or his Justice Dept. Secretary) creates a political firestorm by firing Mueller.

What’s Next for US-China Trade?

What Trump is doing is what US capitalists periodically have done throughout the post-1945 period: i.e. change rules of the game in order to ensure US corporate interests are once again firmly in the drivers’ seat of the global economy for at least another decade and to ensure US global political hegemony remains unchallenged. Nixon did it in 1971-73 targeting European challengers. Reagan did it in 1985 targeting Japan. Now Trump is replaying a similar scenario, targeting China. But China may prove a more difficult adversary for the US in trade negotiations. The US is relatively weaker today than it was in 1971 and 1985; moreover, China is in a far stronger position today relative to the US than were Europe and Japan earlier.

China is not as economically or politically dependent on the US in 2018 as was Japan in 1985. Nor as fragmented and decentralized as was Europe in 1971. Both Japan and Europe were also politically dependent on the US for their military defense at the time. China today is none of the above. Thus the US lacks important levers in negotiations with China it formerly had with Europe and Japan. Not only is China not economically or politically as dependent, but Trump’s initial $150 billion of US tariffs levied on China represents only 2.4% of all China trade with the world. It will therefore take more than US tariffs, even the $400+ billion of Trump’s total threatened tariffs on China, to get China to capitulate on trade as Japan did in 1985—a capitulation that eventually wrecked Japan’s economy and led in part to Japan’s 1991 financial implosion as a consequence.

And there’s the matter of North Korea. If the US expects China’s ‘help’ in getting North Korea to the negotiating table and de-nuclearizing the regime, it certainly won’t get it by provoking a trade war with China.

China has notable cards to play in its economic deck. For one thing, it could significantly slow its purchases of US Treasury bonds. That would require the US central bank to raise rates even further to entice other sources to buy the bonds China would have. That will pressure US interest rates to rise even further, and slow the US economy even more so than otherwise. China could also reverse its policy of keeping the value of its currency, the Yuan, high. A downward drift of the Yuan would raise the value of the dollar and thus make US exports less competitive. It could impose more rules on US corporations in China, give import licenses to European or other competitors, hold up mergers and acquisitions worldwide involving US corporations.

Another response by China might be to raise the requirements of technology transfer for US corporations located in China. There’s a long term strategic race between China and the US over who’ll come to dominate the new technologies—especially Artificial Intelligence, 5G wireless, and cyber security tech. China files about the same number of patents as the US every year, with Germany third and the rest of the world well behind. Who files the most AI, 5G and other patents may prove the winner in future global economic power. AI, 5G, cyber security are the technology that will ensure military dominance for years to come. The US sees China as its biggest threat in this sphere. The US wants to prevent China from capturing these critically strategic technologies. Trump China trade policy is thus inseparable from a US policy of launching a new military Cold War with China.

The outcome of the Trump-Xi Buenos Aires meeting in late November 2018 was an agreement by Trump to suspend raising tariffs on the second $100 billion, from current 10% to 25%, and in addition to impose an additional 25% on the remaining $267 billion of China goods—all by January 1, 2019. Instead it was agreed to continue negotiating again for another 90 days, until March 2. In return, China agreed in Buenos Aires to what it had already ‘put on the table’ during 2018: to open its markets to 51% foreign ownership and buy more US farm products.

Mid-level US-China trade delegations met in Beijing and began negotiations once again. By mid-January China clarified and added further concessions: It publicly declared it would purchase a $1 trillion more in US products over the course of the next six years. That’s apparently in addition to the already several hundred billions of dollars annually it purchases in US goods and services. It began buying US soybeans again, conceded to buy for the first time US GMO farm products, and to increase its purchase of US energy. It announced lower tariffs on US car imports, began awarding companies 51% ownership officially and scheduled to pass a new foreign investment law by January 29. It also has reportedly amended its laws to ban enforced tech transfer in China.

Despite China’s major concessions to date, the Lighthizer-Hawks-Military Industrial Complex faction has continued to push its hard line. With friends in Congress, the US has attacked the China corporation, Huawei, in an escalation greater than the prior attack on China’s ZTE corporation. It has even gotten US allies in Europe and Canada to initiate bans on Huawei as well. The US ally, Canada, arrested Huawei’s co-chairperson, while in Canada and is holding her as a common criminal. This has provoked counter-arrests of Canadians in China in return. The Huawei events likely represent attempts by US trade hardliners to scuttle again any potential agreement between the US and China by March 2. The fighting within the US trade factions also continues. US Treasury Secretary, Mnuchin, on January 17, 2019 publicly floated the proposal to lift all US tariffs on China as a concession in the negotiations. This has enraged the Lighthizer-Military faction in the US. The outcome is still uncertain. Lighthizer-Navarro still technically lead the US negotiations and will be the lead negotiators with China’s Vice-Premier for trade, Liu He, who is scheduled to come to Washington on January 30 to begin high level discussions. Whether Mnuchin and US big corporations and bankers can prevail with Trump and get a deal, or whether the Lighthizer faction can convince Trump the tech issue concessions by China are not sufficient for a deal, remains to be determined.

This writer has predicted, and continues to predict, that a trade deal will be reached between the two, given that the US (and China) and global economies will continue over the long run to slow, and a global recession is on the horizon by 2020 and perhaps earlier by late 2019. The anti-China factor, Lighthizer &Co., do not want a trade deal. They want trade as an issue that pushes US and China toward a new Cold War. Whether US bankers and big business can demand the US and Trump accept China’s significant economic concessions will determine the outcome as well. A final deal is in no way assured, however, given Trump’s instability and the fact he has surrounded himself with neocon advisors and sycophant, lightweight cabinet replacements. In the end they may prevail and get their China-US Cold War.

Dr. Jack Rasmus

November 19, 2019

Unlike Trump’s trade ‘war’ with US allies, which has always been ‘phony’ (see Part 1 of this article). Trump never envisioned major changes in US trade relations with US allies, starting with South Korea, then NAFTA trade partners, Mexico and Canada. Tariffs on steel and aluminum were offset by more than 3000 exemptions announced by the Trump administration. Tariffs on European autos, threatened by Trump, were suspended. And trade negotiations with Japan were left unscheduled.

Before the November 2018 US midterm Congressional elections, Trump sought just token adjustments to US-ally trade relations that he then exaggerated and boasted to his US domestic political base, claiming his ‘America First’ economic nationalism policies were delivering results. China-US trade was another matter.

On the surface, the China-US dispute appeared as the US attempting to reduce the trade deficit with China—although that US trade deficit with China had not changed much for the past several years. A second apparent US objective was the US long-standing demand that China open its markets to US business, which meant that China should allow US companies a greater than 50% ownership of their operations in China, especially US banks and financial corporations. But reducing the trade deficit and opening China markets were secondary objectives. The primary US objective, that became increasingly apparent over the course of 2018, was to prevent, or at least slow, China’s ‘2025’ technology development program. That program focused on next generation technologies like AI, cybersecurity and 5G wireless—the technologies of the future that new industries would be built upon. And, equally important, the technologies that would determine military dominance by 2030.

The primary US objective, that became increasingly apparent over the course of 2018, was to prevent, or at least slow, China’s ‘2025’ technology development program.Throughout 2018 three factions within the US trade negotiation team would ‘fight it out’ over which of the three objectives of US-China trade relations would prove primary: reducing the trade deficit (mostly by China buying more US farm products from US agribusiness companies); allowing US corporations, especially banks, to have majority ownership and control of their operations in China; or US forcing China to stop its technology transfer and slow its nextgen technology development and thereby reduce the threat to US military dominance over the 2020s decade. A major faction fight roiled within the US trade team. The main contention was between the banking interests, led by ex-Goldman Sachs senior manager, US Treasury Secretary, Steve Minuchin, and on the other hand the anti-China hawks, reflecting US military industrial complex and Pentagon interests, led by US Trade Ambassador, Robert Lighthizer, and his allies, anti-China advisor to Trump, Peter Navarro, and later, Trump’s national security advisor, John Bolton.

What follows is Part II of the analysis of Trump’s Déjà vu China-US trade ‘war’ from last March 2018 through mid-January 2019.

The Real Trade War: China Technology

Trump’s trade strategy in relation to China has always been to pressure China on technology transfer and slow its nextgen technology development. Reducing the US-China trade deficit and getting China to open its markets to US financial interests have been objectives as well, but of secondary importance.

Early in 2018 China signaled publicly it would buy $100 billion a year more US products and open its markets to US corporate majority 51% or more ownership. It even granted 51% ownership to select global companies while negotiations with the US were underway. But it refused to make concessions on the technology issue. US defense companies, the Pentagon, the US military-industrial complex interests on the one hand, and US banks on the other, are the major players in determining US trade policy.

Throughout 2018 US trade policy is best described as schizophrenic. Was it Trump driving policy? His anti-China neocons and hawk advisors–Lighthizer, Navarro, and later John Bolton, appointed to the post of National Security Advisor to Trump in 2018, who later joined the administration? Was it Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, who represents US banking and multinational corporate interests on the US trade team? Larry Kudlow, Trump’s interface to his domestic base? And what about Jared Kushner, son-in-law of Trump who has Trump’s closest ear, who has been serving as Trump’s interface to the three major factions on the US trade team? Throughout 2018, the factions contended for Trump’s support, with influence shifting and fluid among the various factions.

Pre-negotiations with China started in early March with Trump’s announcement of the steel-aluminum tariffs. After the tariff announcement, Trump began tweeting the idea that China should reduce its imports to the US by $100 billion. A day after the Office of US Trade Representative (OUST report) was issued by chief Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, Trump announced tariffs of $50 billion on China imports recommended by Lighthizer. However, a window of at least 60 days was required before any definition of the $50 billion or actual implementation by the US might occur, giving ample time for unofficial negotiations to occur between the countries’ trade missions. (Technically, the US could even wait for another six months before actually implementing any tariffs). Announcing intent to a dollar amount of tariffs is one thing; providing a list and definition of what goods would be tariffed is another; and setting a date they would take effect is still another.

China immediately sent its main trade negotiator, Liu He, to Washington and assumed a cautious, almost conciliatory approach at first. China responded initially in March with a modest $3 billion in tariffs on US exports. It also made it clear the $3 billion was in response to US steel and aluminum tariffs previously announced by Trump, and not Trump’s $50 billion tariff threat specifically targeting China. But China noted more action could follow, as it forewarned it was considering additional tariffs of 15% to 25% on US products, especially agricultural, in response to Trump’s $50 billion announcement.

China was waiting to see the US details. At the same time in April it signaled it was willing to open China brokerages and insurance companies to US 51% ownership (and possibly even 100% within three years). It also announced it would buy more semiconductor chips from the US instead of Korea or Taiwan. It was all a carefully crafted public response, designed not to escalate trade negotiations with the Trump administration prematurely. A series of token concessions and minimal tariff responses.

Behind the scenes China and US trade representatives continued to negotiate. By the end of March, all that had actually had occurred was Trump’s announcement of $50 billion in tariffs on China imports, but without details, plus China’s $3 billion token response to prior US steel-aluminum tariffs. From there, however, events began to deteriorate.

On April 3, 2018 Trump defined his threat of $50 billion of tariffs—25% on a wide range of 1300 of China’s consumer and industrial imports to the US. It was Lighthizer’s OUST Report’s recommended March list that launched Trump’s trade offensive with China. Influential business groups in the US, like the Business Roundtable, US Chamber of Commerce, and National Association of Manufacturers immediately criticized the move, calling for the US instead to work with its allies to pressure China to reform—not to use tariffs as the trade reform weapon. The anti-China hardline US factor brushed aside the criticism.

China now responded more firmly, promising an equal tariff response, declaring it was not afraid of a trade war with the US. That was an invitation for a Trump tweet and declaration he believed the US would not “lose a trade war” with China and maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to have one. He suggested that another $100 billion in US tariffs might get China’s attention.

China’s initial $3 billion tariffs, and China’s suggestion of more billions of 15%-25% tariffs, targeted US companies and agricultural production in Trump’s Midwest political base. This may have especially aggravated Trump, disrupting his plans to mobilize that base for domestic political purposes before the November 2018 elections. Trump’s typical approach to negotiating—employed repeatedly during his private business dealings before being elected—is to never let his adversary ‘one up’ him, as they say. He always keeps raising the stakes until the other side stops matching his demands. Then he negotiates back to original positions, controlling the negotiating agenda and maintaining the upper hand in the process.

Trump’s typical approach to negotiating—employed repeatedly during his private business dealings before being elected—is to never let his adversary ‘one up’ him, as they say. He always keeps raising the stakes until the other side stops matching his demands.China initially fell into Trump’s trap, responding to Trump’s $50 billion of tariffs announcement with its own $50 billion tariffs on 128 US imports to China. This time targeting US agricultural products and especially US soybeans, but also cars, oil and chemicals, aircraft and industrial productions—the production of which is also heavily concentrated in the Midwest US. China noted further it was prepared to announce another $100 billion in tariffs as well if Trump followed through with his threat of imposing $100 billion more tariffs. In less than a month, the character of negotiations had shifted.

In response to the ‘tit for tat’ tariff threats, the US stock markets plummeted during the first week of April. Trump advisors, Larry Kudlow and Steve Mnuchin, intervened publicly to dampen the effect of Trump’s remarks on the markets. Kudlow tried to assure investors, “These are just first proposals…I doubt that there will be any concrete actions for several months”. Kudlow said negotiations were continuing. The stock markets recovered again.

But who were investors supposed to believe—Trump or his advisors? They seemed to be talking in different directions. And how long would investors continue to believe the Kudlows and others that matters (and Trump) were under control, and there would be no trade war? China representatives noted that, contrary to Kudlow’s assurances to US markets and investors, there were no ongoing discussions between the two countries.

By the end of the first week of April, US trade objectives and strategy was becoming increasingly murky: US multinational businesses restated what they wanted was more access to China markets. US defense establishment, NSA and the Pentagon, and the Trump administration ‘hawks’—Lighthizer, John Bolton and Peter Navarro—retorted they wanted an end to strategic technology transfer to China—both from US companies doing business in China and from China companies purchasing or partnering with American companies in the US.

It appeared what Trump himself wanted anything was something to exaggerate and brag about to his domestic political base emphasizing nationalist themes—to keep his popular ratings growing, to ensure Republican retention of seats in Congress in the November elections, and to whip up his base.

So what was the real US priority? Whose trade war was it? The neocons and China hawks aligned with the US military-industrial complex? Midwest agribusiness and manufacturing interests? Or US finance capital wanting to escalate its penetration of China markets?

However, by mid-April it was all still talk, with tariffs actions on paper, and not yet implemented. The next step would be defining the announced tariffs in detail. Announcing tariffs was only like waving a gun, to use a metaphor. Defining the tariffs was like loading a gun, putting the ‘safety’ lock on, but not yet pulling the trigger. Tariff implementation dates were when the shoot-out would really begin.

As of mid-April the negotiations by trade representatives continued in the background, while US capitalists in the Business Roundtable and other prime corporate organizations added their input to the public commentary process that was scheduled to continue in the US until May 22.

US Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, went to Beijing in the weeks prior to May 22. He returned declaring there was an agreement. Mnuchin kicked Peter Navarro, one of the hawks, from the US trade team. The China hawks and military industrial complex immediately responded, with help of their friends in Congress. They went after China’s ZTE corporation doing business in the US, charging it with technology espionage and transfer. The tech faction on the US trade team took over from Mnuchin. Navarro was put back. Any tentative deal was scuttled.

What happened in the subsequent six months from June to November 2018 was a steady escalation of threats, and subsequent actions, by Trump to raise tariffs, while he simultaneously kept saying his relationship with China president Xi was great and he expected a trade deal at some point: His response to China’s $50 billion tariff announcement—the counter to Trump’s $100 billion more tariffs—was to publicly declare the US should consider an additional $100 billion in tariffs. The additional $100 billion were implemented thereafter.

China again responded tit-for-tat, as its Commerce Ministry spokesman, Gao Feng, declared it would not hesitate to put in place ‘detailed countermeasures’ that didn’t ‘exclude any options’. And, in the most ominous comment to date, it was made clear that should Trump impose the additional $100 billion, ‘China would not negotiate’! And as China Foreign Ministry spokesman, Geng Shuang, following up Gao Feng, indicated in an official news briefing, “The United States with one hand wields the threat of sanctions, and at the same time says they are willing to talk. I’m not sure who the United States is putting on this act for”…Under the current circumstances, both sides even more cannot have talks on these issues”.

Trump’s $150 billion in tariffs on China was played to his domestic political base, in the weeks prior to the November midterm US elections, as evidence of his tough policy of US economic nationalism. Trump further announced reaching an agreement with Mexico and Canada replacing the NAFTA free trade deal—exaggerating and spinning the new terms and conditions as major improvements while, in fact, the details were token much like the prior changes to the US-South Korean free trade agreement. No new tariffs were implemented on Mexican goods imports to the US.

Trump’s $150 billion in tariffs on China was played to his domestic political base, in the weeks prior to the November midterm US elections, as evidence of his tough policy of US economic nationalism.Trump tried desperately to get the Chinese to return to the negotiating table during the months immediately preceding the US elections. However, China refused to be ‘played’ like Mexico and Canada for Trump’s election objectives and refused to return.

Trump threatened to raise tariffs on the second $100 billion implemented, from 10% to 25% and threatened another 25% on an additional $200 billion in China imports. Still no China agreement to negotiate.

By the early fall 2018 it was clear that the China hawks—Lighthizer, the military-industrial complex-the Pentagon & Co.—were in control of Trump trade policy. Regardless of China concessions on reducing the trade deficit or granting 51% access to its markets, their primary demand was slowing (or ideally subverting) China technology develop—stopping tech transfer in China and elsewhere in the US, as well as among US allies. The side-lining of Mnuchin over the summer, the restoration of Navarro to the trade team, and the adding of notorious anti-China hawk, John Bolton, all strengthened the tech development faction, led by Lighthizer, on the US trade team. They were in effect in control as the US midterm elections approached.

By the early fall 2018 it was clear that the China hawks—Lighthizer, the military-industrial complex-the Pentagon & Co.—were in control of Trump trade policy.In the run-up to the US elections it was also clear Trump was focused on his domestic political base, repeatedly tweeting his ultra- economic nationalist rhetoric. Trump’s nationalist rhetoric also contributed to preventing the relaunch of trade negotiations with China. Part of this threatening rhetoric included Trump public statements that he would implement a third round of $200 billion more 25% tariffs by January 1, 2019 on China. In that environment of escalating threats, anti-China hardliners clearly in control of US policy, and pending US elections, it was virtually impossible China would agree to negotiate.

Following the November US elections, a meeting was now possible. The G20 nations gathering in Buenos Aires scheduled for late November presented the opportunity. Intense maneuvering occurred between the anti-China technology hawks and the Mnuchin bankers-multinational corporations factions. Lighthizer released a new report criticizing China tech policy and appeared to have the upper hand and opposed a meeting between Trump and China president, Xi, at a side venue dinner in Buenos Aires. That reflected a new effort and breakthrough by the Mnuchin faction of big US banks, tech, and aerospace corporations. From mid-October through November the US stock markets began a precipitous fall, which would continue through December, and amount to the worst stock correction since 2008 and even 1931. That financial and the real slowing of the US housing, construction, and auto industries likely shifted Trump administration strategy. The momentum of negotiations strategy began to shift from the Ligthizer faction.

Elements of Trump Trade Strategy

Apart from the three main objectives of Trump China trade policy noted—i.e. China purchases of more US goods, opening markets to 51% ownership for banks and other US corporations, and the nextgen tech development issue—there are various additional objectives behind the strategy.

First, the steel-aluminum tariffs that launched the Trump trade offensive in March 2018 were a signal to US competitors that they should prepare to ‘come to the table’ and renegotiate current trade arrangements, since the US now plans to change the rules of the game again—just as Reagan and Nixon did before in the 1970s and 1980s. But once they ‘came to the table’, the changes in rules of the game with regard to trade relations with US allies did not result in a fundamental restructuring of the US-allies trade relations. The South Korean deal (see Part 1 of this article), the following revised NAFTA treaty, the suspension of negotiations on auto and other tariffs with Europe and Japan, plus the thousands of exemptions to steel and other tariffs allowed by the Trump administration to date all reveal that trade renegotiation with US allies is mostly for show. However, the effort throughout 2018 all made for good campaign speech ‘economic nationalist’ hyperbole in an election year.

Trump simply does not have the kind of leverage over China negotiations in 2018-19 that Reagan had over Japan in the 1980s and even Nixon had in the early 1970s with Europe.Trump has been pursuing a ‘dual track’ trade offensive: a ‘softball’ approach to US allies and an increasingly hard line with China. However, by January 2019 it appears the China hardline track may also fall well short of the threats and hyperbole to date. Trump simply does not have the kind of leverage over China negotiations in 2018-19 that Reagan had over Japan in the 1980s and even Nixon had in the early 1970s with Europe.

A second development impacting Trump trade strategy has to do with the inevitable slowing of the US real economy in 2019-20. The floodgates of fiscal policy have been reopened in 2018 with Trump’s $4.5 trillion corporate and investor tax cuts, plus hundreds of billions $ more in defense and war spending hikes. Annual deficits of more than $1 trillion a year for another decade are now baked into the US budget. The deficits in turn have required the Federal Reserve US central bank to raise interest rates to fund those annual trillion dollar and more deficits and debt. It is becoming increasingly clear that the Trump tax cuts have not stimulated real US economic growth very much. Most of the $4.5 trillion business-investor tax cuts are going toward buying back corporate stock ($590 billion forecast 2018 by Goldman Sachs), paying out more dividends ($400 billion plus forecast), and financing record levels of merger & acquisition deals ($1.2 trillion in 2018)..

It is becoming increasingly clear that the Trump tax cuts have not stimulated real US economic growth very much. [...] Trump needs desperately to get an agreement with China, to avert a trade war, and boost trade as the US economy slows.In short, rising interest rates, ineffective tax cuts not producing projected real investment and growth, and escalating annual deficits and debt will need a major expansion of US trade exports to offset the rate hikes, deficits, and inevitable slowing US economy by late 2019. Trump needs desperately to get an agreement with China, to avert a trade war, and boost trade as the US economy slows.

Third, Trump trade policy comes as global trade has been slowing. Global commodity prices are in retreat once again. 2017’s much hyped ‘synchronized’ global recovery is falling apart—in Europe, Japan and key emerging market economies as well. Another recession is coming, possibly as early as late 2019 and certainly no later than 2020. So US trade policy is shifting, attempting to ensure that US business interests retain their share of what will likely be a slower growing (or even declining) world trade pie. Trump and US business are repositioning before the global cycle next turns down.

US domestic and global economic objectives are not the only forces influencing Trump’s trade policy. There are just as important US political objectives behind it as well.

Trade policy is about Trump re-election strategy as much as anything else—including trade deficits, market access, and tech transfer.The 2018 tariff announcements represent Trump’s leap into his 2020 re-election campaign, a return to intense nationalist themes, and a move to mobilize his domestic political base once again around nationalist appeals. Electoral politics are also in play here, in other words. The steel and aluminum tariffs were announced within 48 hours of Trump’s speaking to the ‘America First’ coalition of ultra-conservative and aggressive capitalist interest groups that were meeting in Washington the same week of the steel-aluminum tariff announcements. The ‘American Firsters’ promised to raise $100 million for his re-election campaign; Trump rewarded them within hours of their meeting and financial commitment to his campaign with his latest bombast on trade. Escalating threats and implementing tariffs on China in 2018 also cannot be separated from Trump efforts to influence the outcomes of the 2018 November midterm elections. Trade policy is about Trump re-election strategy as much as anything else—including trade deficits, market access, and tech transfer.

Less obvious perhaps is Trump’s leveraging of trade policy and nationalist themes as a way to agitate and mobilize his base, in preparation to counter the Mueller investigation once it’s concluded. As a possible Mueller indictment of Trump approaches, Trump has been clearly preparing his base. He is also cleaning house within his administration, surrounding himself with like-minded aggressive conservatives, former Neocons, and various sycophants—in anticipation of the ‘street fight’ he’s preparing for with the traditional liberal elite in the US once he (or his Justice Dept. Secretary) creates a political firestorm by firing Mueller.

What’s Next for US-China Trade?

What Trump is doing is what US capitalists periodically have done throughout the post-1945 period: i.e. change rules of the game in order to ensure US corporate interests are once again firmly in the drivers’ seat of the global economy for at least another decade and to ensure US global political hegemony remains unchallenged. Nixon did it in 1971-73 targeting European challengers. Reagan did it in 1985 targeting Japan. Now Trump is replaying a similar scenario, targeting China. But China may prove a more difficult adversary for the US in trade negotiations. The US is relatively weaker today than it was in 1971 and 1985; moreover, China is in a far stronger position today relative to the US than were Europe and Japan earlier.

China is not as economically or politically dependent on the US in 2018 as was Japan in 1985. Nor as fragmented and decentralized as was Europe in 1971. Both Japan and Europe were also politically dependent on the US for their military defense at the time. China today is none of the above. Thus the US lacks important levers in negotiations with China it formerly had with Europe and Japan. Not only is China not economically or politically as dependent, but Trump’s initial $150 billion of US tariffs levied on China represents only 2.4% of all China trade with the world. It will therefore take more than US tariffs, even the $400+ billion of Trump’s total threatened tariffs on China, to get China to capitulate on trade as Japan did in 1985—a capitulation that eventually wrecked Japan’s economy and led in part to Japan’s 1991 financial implosion as a consequence.

And there’s the matter of North Korea. If the US expects China’s ‘help’ in getting North Korea to the negotiating table and de-nuclearizing the regime, it certainly won’t get it by provoking a trade war with China.

China has notable cards to play in its economic deck. For one thing, it could significantly slow its purchases of US Treasury bonds. That would require the US central bank to raise rates even further to entice other sources to buy the bonds China would have. That will pressure US interest rates to rise even further, and slow the US economy even more so than otherwise. China could also reverse its policy of keeping the value of its currency, the Yuan, high. A downward drift of the Yuan would raise the value of the dollar and thus make US exports less competitive. It could impose more rules on US corporations in China, give import licenses to European or other competitors, hold up mergers and acquisitions worldwide involving US corporations.

Another response by China might be to raise the requirements of technology transfer for US corporations located in China. There’s a long term strategic race between China and the US over who’ll come to dominate the new technologies—especially Artificial Intelligence, 5G wireless, and cyber security tech. China files about the same number of patents as the US every year, with Germany third and the rest of the world well behind. Who files the most AI, 5G and other patents may prove the winner in future global economic power. AI, 5G, cyber security are the technology that will ensure military dominance for years to come. The US sees China as its biggest threat in this sphere. The US wants to prevent China from capturing these critically strategic technologies. Trump China trade policy is thus inseparable from a US policy of launching a new military Cold War with China.

The outcome of the Trump-Xi Buenos Aires meeting in late November 2018 was an agreement by Trump to suspend raising tariffs on the second $100 billion, from current 10% to 25%, and in addition to impose an additional 25% on the remaining $267 billion of China goods—all by January 1, 2019. Instead it was agreed to continue negotiating again for another 90 days, until March 2. In return, China agreed in Buenos Aires to what it had already ‘put on the table’ during 2018: to open its markets to 51% foreign ownership and buy more US farm products.

Mid-level US-China trade delegations met in Beijing and began negotiations once again. By mid-January China clarified and added further concessions: It publicly declared it would purchase a $1 trillion more in US products over the course of the next six years. That’s apparently in addition to the already several hundred billions of dollars annually it purchases in US goods and services. It began buying US soybeans again, conceded to buy for the first time US GMO farm products, and to increase its purchase of US energy. It announced lower tariffs on US car imports, began awarding companies 51% ownership officially and scheduled to pass a new foreign investment law by January 29. It also has reportedly amended its laws to ban enforced tech transfer in China.

Despite China’s major concessions to date, the Lighthizer-Hawks-Military Industrial Complex faction has continued to push its hard line. With friends in Congress, the US has attacked the China corporation, Huawei, in an escalation greater than the prior attack on China’s ZTE corporation. It has even gotten US allies in Europe and Canada to initiate bans on Huawei as well. The US ally, Canada, arrested Huawei’s co-chairperson, while in Canada and is holding her as a common criminal. This has provoked counter-arrests of Canadians in China in return. The Huawei events likely represent attempts by US trade hardliners to scuttle again any potential agreement between the US and China by March 2. The fighting within the US trade factions also continues. US Treasury Secretary, Mnuchin, on January 17, 2019 publicly floated the proposal to lift all US tariffs on China as a concession in the negotiations. This has enraged the Lighthizer-Military faction in the US. The outcome is still uncertain. Lighthizer-Navarro still technically lead the US negotiations and will be the lead negotiators with China’s Vice-Premier for trade, Liu He, who is scheduled to come to Washington on January 30 to begin high level discussions. Whether Mnuchin and US big corporations and bankers can prevail with Trump and get a deal, or whether the Lighthizer faction can convince Trump the tech issue concessions by China are not sufficient for a deal, remains to be determined.

This writer has predicted, and continues to predict, that a trade deal will be reached between the two, given that the US (and China) and global economies will continue over the long run to slow.Which faction succeeds influencing Trump will determine the outcome. Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and interface between the two factions, may play a decisive role as well. It is highly unlikely a deal will be struck January 30 or soon after. The key will be how far China is willing to go with tech concessions. And whether the wording will satisfy the Lighthizer anti-China hawks who want a Cold War with China. Thus US military policy may be the deciding factor in any US-China trade deal. Negotiations will almost certainly continue up to the March 2, 2019 deadline. They may even be extended. Much will depend on the condition of the US and China economies in the coming months (and the US stock markets which Trump absurdly sees as the key indicator of US economic health).

This writer has predicted, and continues to predict, that a trade deal will be reached between the two, given that the US (and China) and global economies will continue over the long run to slow, and a global recession is on the horizon by 2020 and perhaps earlier by late 2019. The anti-China factor, Lighthizer &Co., do not want a trade deal. They want trade as an issue that pushes US and China toward a new Cold War. Whether US bankers and big business can demand the US and Trump accept China’s significant economic concessions will determine the outcome as well. A final deal is in no way assured, however, given Trump’s instability and the fact he has surrounded himself with neocon advisors and sycophant, lightweight cabinet replacements. In the end they may prevail and get their China-US Cold War.

Dr. Jack Rasmus

November 19, 2019

| Top image: President Donald J. Trump and First Lady Melania Trump arrive in China | November 8, 2017 (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead). From: flickr |

|---|

Comments

Post a Comment

Your thoughts...